There are many types of hearing aids (also known as hearing instruments), which vary in size, power and circuitry. Among the different sizes and models are:

This was the first type of hearing aid invented by Harvey Fletcher while working at Bell Laboratories.[3] Body aids consist of a case and an earmold, attached by a wire. The case contains the electronic amplifier components, controls and battery while the earmold typically contains a miniature loudspeaker. The case is typically about the size of a pack of playing cards and is carried in a pocket or on a belt. Without the size constraints of smaller hearing devices body worn aid designs can provide large amplification and long battery life at a lower cost. Body aids are still marketed in emerging markets because of their lower cost.

This was the first type of hearing aid invented by Harvey Fletcher while working at Bell Laboratories.[3] Body aids consist of a case and an earmold, attached by a wire. The case contains the electronic amplifier components, controls and battery while the earmold typically contains a miniature loudspeaker. The case is typically about the size of a pack of playing cards and is carried in a pocket or on a belt. Without the size constraints of smaller hearing devices body worn aid designs can provide large amplification and long battery life at a lower cost. Body aids are still marketed in emerging markets because of their lower cost.

BTE aids consist of a case, an earmold or dome and a connection between them. The case contains the electronics, controls, battery, microphone(s) and often the loudspeaker. Generally, the case sits behind the pinna with the connection from the case coming down the front into the ear. The sound from the instrument can be routed acoustically or electrically to the ear. If the sound is routed electrically, the speaker (receiver) is located in the earmold or an open-fit dome, while acoustically coupled instruments use a plastic tube to deliver the sound from the case’s loudspeaker to the earmold.

BTEs can be used for mild to profound hearing loss. As the electrical components are located outside the ear, the chance of moisture and earwax damaging the components is reduced, which can increase the durability of the instrument. BTEs are also easily connected to assistive listening devices, such as FM systems, to directly integrate sound sources with the instrument. BTE aids are commonly worn by children who need a durable type of hearing aid.

BTE hearing instruments that place the loudspeaker directly in the ear without a fitted earmold are often referred to as “Receiver in the Canal” instruments. These instruments use soft ear inserts, typically of silicone, to position the loudspeaker in the patient’s ear.

Some of the advantages with this approach include improved sound quality, reduced case size, “open-fit” technology, and immediate patient fitting.

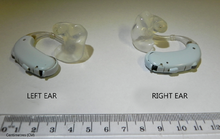

An earmold is created from an impression taken of the individual's outer ear. This usually ensures a comfortable fit and reduces the possibility of feedback. Earmolds are made from a variety of hard (firm) and soft (pliable) materials. The color of the case and earmold of a BTE aid can be modified and optional decorations can be added.

These devices fit in the outer ear bowl (called the concha); they are sometimes visible when standing face to face with someone. ITE hearing aids are custom made to fit each individual's ear. They can be used in mild to some severe hearing losses. Feedback, a squealing/whistling caused by sound (particularly high frequency sound) leaking and being amplified again, may be a problem for severe hearing losses. Some modern circuits are able to provide feedback regulation or cancellation to assist with this. Venting may also cause feedback. A vent is a tube primarily placed to offer pressure equalization. However, different vent styles and sizes can be used to influence and prevent feedback. Traditionally, ITEs have not been recommended for young children because their fit could not be as easily modified as the earmold for a BTE, and thus the aid had to be replaced frequently as the child grew. However, there are new ITEs made from a silicone type material that mitigates the need for costly replacements. ITE hearing aids can be connected wirelessly to FM systems, for instance with a body-worn FM receiver with induction neck-loop which transmits the audio signal from the FM transmitter inductively to the telecoil inside the hearing instrument.

ITC aids are smaller, filling only the bottom half of the external ear. The aid cannot be seen when face to face with the wearer. MIC and CIC aids are generally not visible unless the viewer looks directly into the wearer's ear. These aids are intended for mild to moderately-severe losses. CICs are usually not recommended for people with good low frequency hearing, as the occlusion effect is much more noticeable.

In-the-ear hearing aids are typically more expensive than behind-the-ear counterparts of equal functionality, because they are custom fitted to the patient's ear. In fitting, an audiologist takes a physical impression (mold) of the ear. The mold is scanned by a specialized CAD system, resulting in a 3D model of the outer ear. During modeling, the venting tube is inserted. The digitally modeled shell is printed using a rapid prototyping technique such as stereolithography. Finally, the aid is assembled and shipped to the audiologist after a quality check.

This type of hearing aid fitting is not visible when worn. This is because it fits deeper in the canal than other types, so that it is out of view even when looking directly into the ear bowl (concha). A comfortable fit is achieved because the shell of the aid is custom-made to the individual ear canal after taking a mould. Invisible hearing aid types use venting and their deep placement in the ear canal to give a more natural experience of hearing. Unlike other hearing aid types, with the IIC aid the majority of the ear is not blocked (occluded) by a large plastic shell. This means that sound can be collected more naturally by the shape of the ear, and can travel down into the ear canal as it would with unassisted hearing. Some models allow the wearer to use a mobile phone as a remote control to alter memory and volume settings, instead of taking the IIC out to do this. IIC types are most suitable for users up to middle age, but are not suitable for more elderly people.

Extended wear hearing aids are hearing devices that are non-surgically placed in the ear canal by a hearing professional. The extended wear hearing aid represents the first "invisible" hearing device. These devices are worn for 1–3 months at a time without removal. They are made of soft material designed to contour to each user and can be used by people with mild to moderately severe hearing loss. Their close proximity to the ear drum results in improved sound directionality and localization, reduced feedback, and improved high frequency gain. While traditional BTE or ITC hearing aids require daily insertion and removal, extended wear hearing aids are worn continuously and then replaced with a new device. Users can change volume and settings without the aid of a hearing professional. The devices are very useful for active individuals because their design protects against moisture and earwax and can be worn while exercising, showering, etc. Because the device’s placement within the ear canal makes them invisible to observers, extended wear hearing aids are popular with those who are self-conscious about the aesthetics of BTE or ITC hearing aid models. As with other hearing devices, compatibility is based on an individual’s hearing loss, ear size and shape, medical conditions, and lifestyle. The disadvantages include regular removal and reinsertion of the device when the battery dies, inability to go underwater, earplugs when showering, and for some discomfort with the fit since it is inserted deeply in the ear canal, the only part of the body where skin rests directly on top of bone.

"Open-fit" or "Over-the-Ear" (OTE) hearing aids are small behind-the-ear type devices. This type is characterized by a minimal amount of effect on the ear canal resonances, as it traditionally leaves the ear canal as open as possible, often only being plugged up by a small speaker resting in the middle of the ear canal space. Traditionally, these hearing aids have a small plastic case behind the ear and a small clear tube running into the ear canal. Inside the ear canal, a small soft silicone dome or a molded, highly vented acrylic tip holds the tube in place. This design is intended to reduce the occlusion effect. Conversely, because of the increased possibility of feedback, and because an open fit allows low frequency sounds to leak out of the ear canal, they are limited to moderately severe high-frequency losses. While the design approach is attractive to a general hearing aid user, open-fit devices can by their design have problems when connected to Assistive Listening Devices (ALD's). This problem has been addressed by manufacturers, who provide assistive listening devices that can be paired with the hearing aid.

The personal programmable, consumer programmable, consumer adjustable, or self programmable hearing aid allows the consumer to adjust their own hearing aid settings to their own preference using their own PC. Personal programmable hearing aid manufacturers or dealers can also remotely adjust these types of hearing aids for the customer. Available in all hearing aid styles, these hearing aids differ from traditional hearing aids only in that they are adjustable by the consumer.

Disposable hearing aids are hearing aids that have a non-replaceable battery. These aids are designed to use power sparingly, so that the battery lasts longer than batteries used in traditional hearing aids. Disposable hearing aids are meant to remove the task of battery replacement and other maintenance chores (adjustment or cleanings). To date, two companies have brought disposable hearing aids to market: Songbird Hearing, and Lyric. Songbird is a BTE hearing aid that is bought online and worn like any other BTE device. When it runs out, the user replaces it with a new one. Lyric is implanted deep in the ear canal by a professional. When it runs out, it must be removed and replaced with a new one by a professional.

The BAHA is an auditory prosthetic based on bone conduction which can be surgically implanted. It is an option for patients without external ear canals, when conventional hearing aids with a mould in the ear cannot be used. The BAHA uses the skull as a pathway for sound to travel to the inner ear. For people with conductive hearing loss, the BAHA bypasses the external auditory canal and middle ear, stimulating the functioning cochlea. For people with unilateral hearing loss, the BAHA uses the skull to conduct the sound from the deaf side to the side with the functioning cochlea.

Individuals under the age of two (five in the USA) typically wear the BAHA device on a Softband. This can be worn from the age of one month as babies tend to tolerate this arrangement very well. When the child's skull bone is sufficiently thick, a titanium "post" can be surgically embedded into the skull with a small abutment exposed outside the skin. The BAHA sound processor sits on this abutment and transmits sound vibrations to the external abutment of the titanium implant. The implant vibrates the skull and inner ear, which stimulate the nerve fibers of the inner ear, allowing hearing.

The surgical procedure is simple both for the surgeon, involving very few risks for the experienced ear surgeon. For the patient, minimal discomfort and pain is reported. Patients may experience numbness of the area around the implant as small superficial nerves in the skin are sectioned during the procedure. This often disappears after some time. There is no risk of further hearing loss due to the surgery. One important feature of the Baha is that, if a patient for whatever reason does not want to continue with the arrangement, it takes the surgeon less than a minute to remove it. The Baha does not restrict the wearer from any activities such as outdoor life, sporting activities etc.

A BAHA can be connected to an FM system by attaching a miniaturized FM receiver to it.

Two main brands manufacture BAHAs today - the original inventors Cochlear, and the hearing aid company Oticon.

During the late 1950s through 1970s, before in-the-ear aids became common (and in an era when thick-rimmed eyeglasses were popular), people who wore both glasses and hearing aids frequently chose a type of hearing aid that was built into the temple pieces of the spectacles. However, the combination of glasses and hearing aids was inflexible: the range of frame styles was limited, and the user had to wear both hearing aids and glasses at once or wear neither. Today, people who use both glasses and hearing aids can use in-the-ear types, or rest a BTE neatly alongside the arm of the glasses. There are still some specialized situations where hearing aids built into the frame of eyeglasses can be useful, such as when a person has hearing loss mainly in one ear: sound from a microphone on the "bad" side can be sent through the frame to the side with better hearing.

This can also be achieved by using CROS or bi-CROS style hearing aids, which are now wireless in sending sound to the better side.

Spectacle hearing aids are generally worn by people with a hearing loss who either prefer a more cosmetic appeal of their hearing aids by being attached to their glasses or where sound cannot be passed in the normal way, via a hearing aids, perhaps due to a blockage in the ear canal. pathway or if the client suffers from continual infections in the ear. Spectacle aids come in two forms, bone conduction spectacles and air conduction spectacles.

Bone Conduction Spectacles Sounds are transmitted via a receiver attached from the arm of the spectacles which are fitted firmly behind the boney portion of the skull at the back of the ear, (mastoid process) by means of pressure, applied on the arm of the spectacles. The sound is passed from the receiver on the arm of the spectacles to the inner ear (cochlea), via the bony portion. The process of transmitting the sound through the bone requires a great amount of power. Bone conduction aids generally have a poorer high pitch response and are therefore best used for conductive hearing losses or where it is impractical to fit standard hearing aids. Air Conduction Spectacles Unlike the bone conduction spectacles the sound is transmitted via hearing aids which are attached to the arm or arms of the spectacles. When removing your glasses for cleaning, the hearing aids are detached at the same time. Whilst there are genuine instances where spectacle aids are a preferred choice, they may not always be the most practical option.

Recently, a new type of eyeglass aid was introduced. These 'hearing glasses' feature directional sensitivity: four microphones on each side of the frame effectively work as two directional microphones, which are able to discern between sound coming from the front and sound coming from the sides or back of the user. This improves the signal-to-noise ratio by allowing for amplification of the sound coming from the front, the direction in which the user is looking, and active noise control for sounds coming from the sides or behind. Only very recently has the technology required become small enough to be fitted in the frame of the glasses. As a recent addition to the market, this new hearing aid is currently available only in the Netherlands and Belgium.

A hearing aid and a telephone are "compatible" when they can connect to each other in a way that produces clear, easily-understood sound. The term "compatibility" is applied to all three types of telephones (wired, cordless, and mobile). There are two ways telephones and hearing aids can connect with each other:

Note that telecoil coupling has nothing to do with the radio signal in a cellular or cordless phone: the audio signal picked up by the telecoil is the weak electromagnetic field that is generated by the voice coil in the phone's speaker as it pushes the speaker cone back and forth.

The electromagnetic (telecoil) mode is usually more effective than the acoustic method. This is mainly because the microphone is automatically switched off when the hearing aid is operating in telecoil mode, so background noise is not amplified. Since there is an electronic connection to the phone, the sound is clearer and distortion is less likely. But in order for this to work, the phone has to be hearing-aid compatible. More technically, the phone's speaker has to have a voice coil that generates a relatively strong electromagnetic field. Speakers with strong voice coils are more expensive and require more energy than the tiny ones used in many modern telephones; phones with the small low-power speakers cannot couple electromagnetically with the telecoil in the hearing aid, so the hearing aid must then switch to acoustic mode. Also, many mobile phones emit high levels of electromagnetic noise that creates audible static in the hearing aid when the telecoil is used. A workaround that resolves this issue on many mobile phones is to plug a wired (not Bluetooth) headset into the mobile phone; with the headset placed near the hearing aid the phone can be held far enough away to attenuate the static.

Recent hearing aids include wireless hearing aids. One hearing aid can transmit to the other side so that pressing one aid's program button simultaneously changes the other aid, so that both aids change background settings simultaneously. FM listening systems are now emerging with wireless receivers integrated with the use of hearing aids. A separate wireless microphone can be given to a partner to wear in a restaurant, in the car, during leisure time, in the shopping mall, at lectures, or during religious services. The voice is transmitted wirelessly to the hearing aids eliminating the effects of distance and background noise. FM systems have shown to give the best speech understanding in noise of all available technologies. FM systems can also be hooked up to a TV or a stereo.

2.4 gigahertz Bluetooth connectivity is the most recent innovation in wireless interfacing for hearing instruments to audio sources such as TV streamers or Bluetooth enabled mobile phones. Current hearing aids generally do not stream directly via Bluetooth but rather do so through a secondary streaming device (usually worn around the neck or in a pocket), this bluetooth enabled secondary device then streams wirelessly to the hearing aid but can only do so over a short distance. This technology can be applied to ready-to-wear devices (BTE, Mini BTE, RIE, etc.) or to custom made devices that fit directly into the ear.

Oticon hearing aids for use with Bluetoothwireless devices.

Phonak wireless FM system

ReSound Alera Hearing Aid

ReSound Alera Unite Wireless Accessories

In developed countries FM systems are considered a cornerstone in the treatment of hearing loss in children. More and more adults discover the benefits of wireless FM systems as well, especially since transmitters with different microphone settings and Bluetooth for wireless cell phone communication have become available.

Many theatres and lecture halls are now equipped with assistive listening systems that transmit the sound directly from the stage; audience members can borrow suitable receivers and hear the program without background noise. In some theatres and churches FM transmitters are available that work with the personal FM receivers of hearing instruments.

Most older hearing aids have only an omnidirectional microphone. An omnidirectional microphone amplifies sounds equally from all directions. In contrast, a directional microphone amplifies sounds from in front more than sounds from other directions. This means that sounds originating from the direction the listener is facing are amplified more than sounds coming from behind or other directions. If the speech is in front of the listener and the noise is from a different direction, then compared to an omnidirectional microphone, a directional microphone provides a better signal to noise ratio. Improving the signal to noise ratio improves speech understanding in noise. Directional microphones are the second best method to improve the signal to noise ratio (the best method is an FM system).

Many hearing aids now have both an omnidirectional and a directional microphone. This is because speech often comes from directions other than in front of the listener. Usually, the omnidirectional microphone mode is used in quiet listening situations (e.g. living room) whereas the directional microphone is used in noisy listening situations (e.g. restaurant). The microphone mode is typically selected by using a switch. Some hearing aids automatically switch the microphone mode.

Adaptive directional microphones vary the direction of maximum amplification. The direction of amplification is varied by the hearing aid processor. The processor attempts to provide maximum amplification in the direction of the speech signal. Unless the user manually temporarily switches to a "restaurant program, forward only mode" adaptive directional microphones have a disadvantage of amplifying speech of other talkers in a restaurant. This makes it difficult for the processor to select the desired speech signal. Another disadvantage is that noise often mimics speech characteristics, making it difficult to separate the speech from the noise. Despite the disadvantages, adaptive directional microphones can provide improved speech recognition in noise[17]

Directional microphones only provide benefit when the distance to the talker is small. In contrast, an FM system continues to provide a better signal to noise ratio even at larger speaker to talker distances.[18]

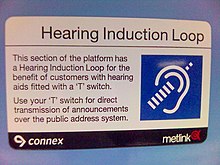

Audio induction loops, sometimes referred to as telecoils or T-coils (from "Telephone Coils"), allow audio sources to be directly connected to a hearing aid, which is intended to help the wearer filter out background noise. They can be used with telephones, FM systems (with neck loops), and induction loop systems (also called "hearing loops") that transmit sound to hearing aids from public address systems and TVs. In the UK and the Nordic countries, hearing loops are widely used in churches, shops, railway stations, and other public places. In the U.S.A., telecoils and hearing loops are gradually becoming more common. Audio induction loops, telecoils and hearing loops are gradually becoming more common also in Slovenia.

A T-coil consists of a metal core (or rod) around which ultra-fine wire is coiled. T-coils are also called induction coils because when the coil is placed in a magnetic field, an alternating electrical current is induced in the wire (Ross, 2002b; Ross, 2004). The T-coil detects magnetic energy and transduces (converts) it to electrical energy. In the United States, the Telecommunications Industry Association's TIA-1083 standard, specifies how analog handsets can interact with telecoil devices, to ensure the optimal performance.[19]

Although T-coils are effectively a wide-band receiver, interference is unusual in most hearing loop situations. Interference can manifest as a buzzing sound, which varies in volume depending on the distance the wearer is from the source. Sources are electromagnetic fields, such as CRT computer monitors, older fluorescent lighting, some dimmer switches, many household electrical appliances and airplanes.

Direct audio input (DAI) allows the hearing aid to be directly connected to an external audio source like a CD player or an assistive listening device (ALD). By its very nature, DAI is susceptible to far less electromagnetic interference, and yields a better quality audio signal as opposed to using a T-coil with standard headphones.

Every electronic hearing aid has at minimum a microphone, a loudspeaker (commonly called a receiver), a battery, and electronic circuitry. The electronic circuitry varies among devices, even if they are the same style. The circuitry falls into three categories based on the type of audio processing (analog or digital) and the type of control circuitry (adjustable or programmable).

Hearing aids are incapable of truly correcting a hearing loss; they are an aid to make sounds more accessible. Two primary issues minimize the effectiveness of hearing aids:

Hearing aids are incapable of truly correcting a hearing loss; they are an aid to make sounds more accessible. Three primary issues minimize the effectiveness of hearing aids: